Food Safety Focus (219th Issue, October 2024) – Article 1

Metallic Contaminants in Food Part I – Lead and Cadmium

Reported by Arthur YAU, Scientific Officer,

Risk Communication Section, Centre for Food Safety

Metals are commonly found naturally in the environment. Metallic contaminants can enter the food supply chain due to pollution of the natural environment (e.g. volcanic activities, industrial activities) or contaminated food during the food production process, hence food may contain trace amounts of metallic contaminants.

Metallic contaminants can enter the human body through various pathways, and diet is one of the important routes. To protect public health and facilitate the international trade of food, like other jurisdictions, maximum levels (MLs) for metallic contaminants such as lead (Pb), cadmium (Cd) and methylmercury (MeHg) have been set for various types of foods that are of significance to the general public. The Codex Alimentarius Commission (Codex), an international organisation under the auspices of the United Nations, has developed many food-related guidelines and standards, including MLs of heavy metals across a wide range of food commodities. The Food Adulteration (Metallic Contamination) Regulations (Cap. 132V) set out the MLs for metallic contaminants in Hong Kong. These MLs are crucial for maintaining food safety and protecting the public from the potential health risks associated with heavy metal exposures. The MLs are the basis of the mechanisms that monitor and regulate the amounts of heavy metals in food.

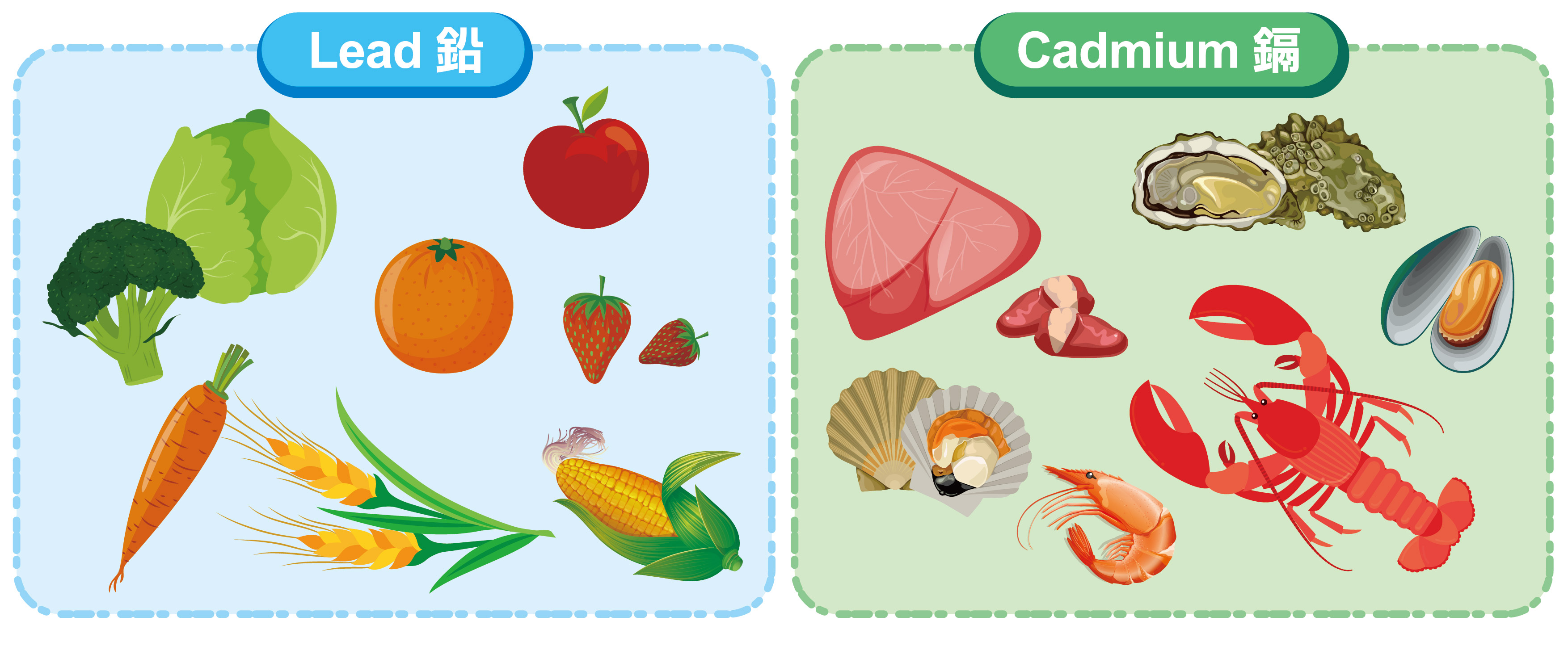

Figure1: Food that may contain cadmium and lead (Cadmium: mammal kidneys and livers (e.g. pigs), oysters, scallops, mussels and crustaceans (e.g. crabs, lobsters and shrimps) )(Lead: crops)

In the following sections, we will briefly discuss the health issues caused by dietary exposure to lead and cadmium.

Lead

Sources and Exposures

Lead is naturally present in the Earth’s crust and is also released through human activities such as mining, smelting, battery production, the use of leaded paint and gasoline and smoking. It can enter the food chain by atmospheric deposition of lead on crops. After ingestion, lead is absorbed through the gastrointestinal tract and deposited in soft tissues and bones.

Toxicity

Exposure to lead can have serious effects for children as it can impair brain development and lead to lower intelligence quotients (IQs), negatively affecting behaviours like attention span, social behaviour and educational attainment. Exposure to lead is also known to cause anaemia, hypertension, renal impairment, immunotoxicity and toxicity to the reproductive organs. Lead absorbed into the body is distributed to the brain, the liver, kidneys and bones. Lead is stored in bones and teeth, where it accumulates over time.

Infants and young children, particularly those under the age of five, and pregnant women are more susceptible to lead exposure than adults. This is due to the fact that children have a higher intake of lead per unit body weight, more dust ingestion, higher absorption in the gastrointestinal tract, a less developed blood-brain barrier, a developing nervous system and a longer life ahead of them for the effects of early lead exposure to manifest. Exposure to high levels of lead in pregnant women can lead to miscarriage, stillbirth, premature birth, low birth weight and minor malformations. The Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA) concluded in 2010 that no health-protective tolerable intake level for lead could be established.

Cadmium

Sources and Exposures

Cadmium also exists naturally in Earth’s crust and is released through volcanic activities, erosions and transportation by river. It is also released through human activities like tobacco smoking, mining, metal refining, burning of fossil fuel, waste incineration (especially cadmium-containing batteries and plastics), manufacture of phosphate fertilizers, recycling of cadmium-containing steel scrap and electrical and electronic wastes and drainage from old mines and waste sites. Cadmium can travel a vast distance to regions far from the sources before it comes down as dust along with rain. For non-smokers, food is the most common source of cadmium exposure. The highest levels of cadmium can be found in the kidneys and livers of animals fed with cadmium-rich diets and in certain species of oysters, scallops, mussels and crustaceans. Although vegetables, cereals and starchy roots crops have lower cadmium levels, they nonetheless contribute to significant cadmium exposure in some countries due to their high consumption amount. Smoking also doubles the cadmium exposure compared with that of non-smokers.

Toxicity

Long-term exposure to cadmium would affect the kidneys, where its accumulation would impact renal tube functions. High intake of cadmium can affect calcium metabolism, leading to the formation of kidney stones and effects on bones. JECFA has established a provisional tolerable monthly intake (PTMI) of 25 μg per kg body weight for cadmium. Acute toxicity of cadmium due to dietary exposure is unlikely.

In the next issue, we will discuss the dietary exposure to methylmecury and its health effects.